The Preacher's Lectionary Notebook - Paul’s Christmas Story in One, Long Sentence

The Second Sunday after Christmas (Year A)

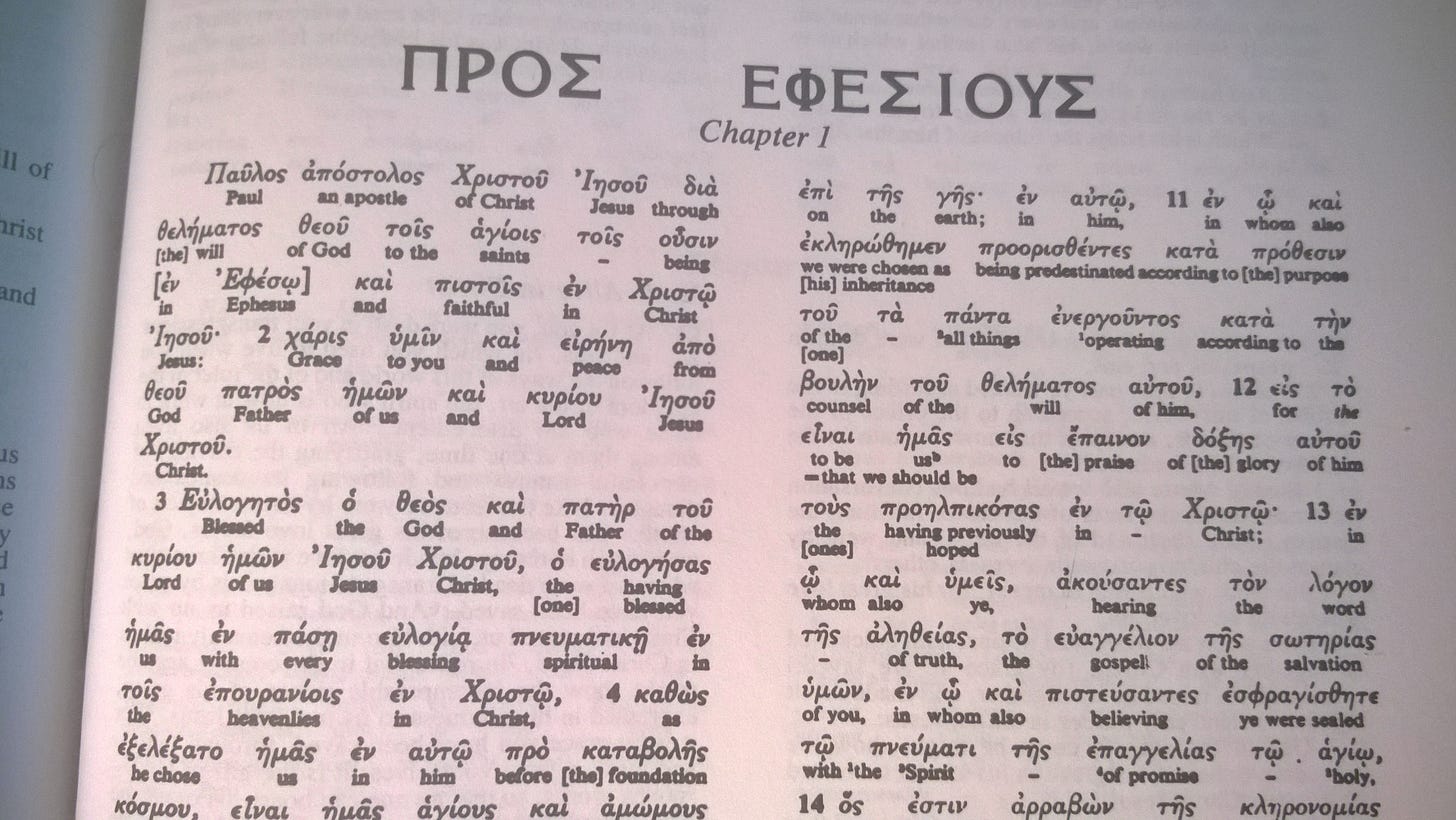

Ephesians 1:3–14 is one long, breathless sentence in the Greek because it is one overflowing thought, a cascade of praise that tumbles forward without stopping to catch its breath. That in itself feels right for Christmas. When God’s plan finally breaks into history in the birth of Jesus, restraint gives way to abundance. Paul begins by blessing God for every spiritual blessing, and the setting for those blessings is firmly “in Christ.” Christmas announces that God’s generosity is not merely spoken from heaven but embodied in a child laid in a feeding trough. The blessings Paul names are not seasonal sentiments; they are the deep realities made visible when the Word becomes flesh.

Paul reaches back before time itself, speaking of election and purpose before the foundation of the world. Christmas often feels small and intimate—candles, carols, quiet nights—but Ephesians insists that the story is cosmic. The child born in Bethlehem is not God improvising a rescue plan but God unveiling a purpose long held in divine love. Being chosen “in Christ” does not sound like a cold decree here; it sounds like belonging, like being wanted before being useful. Christmas carries that same note. The manger says that God’s love precedes achievement, morality, or strength. Grace comes first, wrapped in swaddling cloths.

The passage then turns toward adoption, a word that fits the Christmas story better than it is often allowed. In Christ, God brings outsiders into the family, not grudgingly but joyfully. Christmas narratives are filled with unlikely family gatherings—shepherds, magi, scandal, and surprise all crowded around a newborn. Ephesians echoes this by insisting that God’s plan is relational, not merely legal. Adoption is not just forgiveness of sins but welcome into a household. Christmas proclaims that God is not content to save at a distance; God moves into the neighborhood to make room for others at the table.

Redemption and forgiveness take center stage, grounded in the riches of grace. Christmas can easily be sentimentalized, but Ephesians refuses to separate incarnation from redemption. The baby is born for a purpose that will lead to blood and a cross. Grace is costly, yet freely given. The language of “lavishing” grace fits the Christmas excess of light in darkness, song in silence, and hope in despair. God does not ration mercy; God pours it out with reckless generosity.

Paul then widens the lens again, speaking of God’s mysterious plan to unite all things in Christ, things in heaven and things on earth. Christmas is not only about personal comfort or private faith. It is a declaration that the world’s fragmentation is not the final word. In the birth of Jesus, God commits to healing what is broken, reconciling what is divided, and gathering what has been scattered. The manger quietly announces the coming restoration of all creation.

The passage closes with the gift of the Spirit as a seal and guarantee. Christmas is not a one-day or seasonal event, but the beginning of a life marked by God’s presence. The Spirit assures that the story begun in Bethlehem will be completed. Ephesians 1:3–14, read through Christmas light, becomes a reminder that the season celebrates more than a birth. It celebrates a God who planned, acted, and remains present, drawing the world toward redemption with joy, purpose, and uncontainable grace.

FOR FURTHER EXPLORATION

How does reading Ephesians 1:3–14 alongside the Christmas narratives reshape common understandings of the incarnation as more than a moment of humility, but as the unveiling of a cosmic and eternal plan?

In what ways does Paul’s language of adoption in Ephesians challenge individualistic or sentimental approaches to Christmas and invite a deeper reflection on communal belonging and identity in Christ?

How might the claim that God is “uniting all things in Christ” influence how Christmas is preached, taught, or practiced in a world marked by fragmentation, injustice, and division?