The Preacher's Lectionary Notebook - Shared Surrender to the Crucified Christ

The Third Sunday after the Epiphany (Year A)

The Apostle begins his letter with an appeal—“by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ,”—invoking the highest possible authority, not to silence disagreement but to call the fractured Corinthian community back to a shared center. The problem is not that they have differences; it is that their differences have hardened into rival identities. “I belong to Paul,” “I belong to Apollos,” “I belong to Cephas,” and even the piously aloof “I belong to Christ” all reveal the same disease. The gospel has been turned into a badge of group membership rather than a summons into a cruciform way of life. Paul’s grief is palpable. The church, birthed by the self-giving love of Christ, is now mirroring the competitive, status-driven culture of Corinth rather than offering an alternative to it.

Paul responds to these divisions not by defending his own reputation but by deflating the very logic that makes such rivalries possible. His rhetorical questions cut sharply: “Has Christ been divided? Was Paul crucified for you? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?” The obvious answer—no—exposes the absurdity of their allegiances. The cross cannot be parceled out among personalities. Christ is not a brand, and baptism is not an initiation into a faction. Paul is almost relieved that he baptized only a few of them, lest anyone mistake the sacrament as a pledge of loyalty to him rather than a dying and rising with Christ. Even his brief mention of baptizing the household of Stephanas feels incidental, as though Paul himself is impatient with distractions that pull attention away from the heart of the matter.

That heart is the cross, and Paul insists on keeping it there, even at the cost of appearing unimpressive. He was not sent, he says, to baptize but to proclaim the gospel—and to do so without “wise words,” lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power. This is not a rejection of thoughtfulness or eloquence; it is a refusal to let the gospel be co-opted by the cultural standards of success and persuasion. In Corinth, rhetoric was power. Eloquence established hierarchy. Paul knows that if the gospel is preached as one more form of sophisticated wisdom, it will simply reinforce the very divisions tearing the church apart.

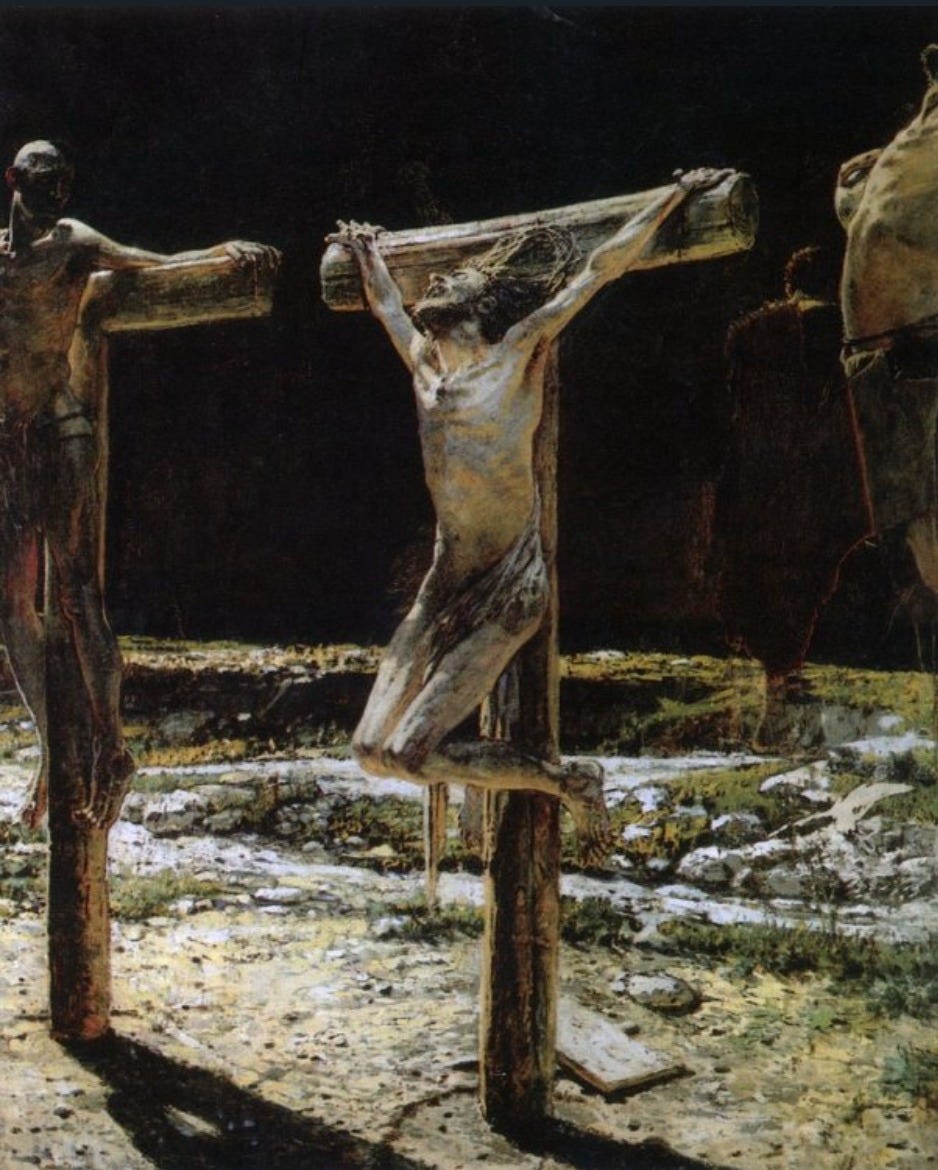

In verse 18, Paul names the fault line running through human history—the word of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to those being saved it is the power of God. The cross exposes the bankruptcy of human boasting and levels all claims to superiority. There is no room here for one-upmanship, no space for spiritual elitism. Everyone stands on the same ground—at the foot of the cross—either scandalized by it or transformed by it. In calling the Corinthians back to unity, Paul is not asking them to agree on everything; he is calling them to remember who they are and how they were saved. Unity, for Paul, does not come from uniformity or strong leadership but from a shared surrender to the strange, unsettling, and life-giving wisdom of the crucified Christ.

FOR FURTHER EXPLORATION

What do Paul’s rhetorical questions (“Was Paul crucified for you?”) reveal about how easily faith can become attached to personalities rather than to Christ himself?

How might “the wisdom of words” still empty the cross of its power in contemporary churches or Christian discourse?

In what practical ways does the message of the cross challenge the sources of division and status-seeking in our own communities today?